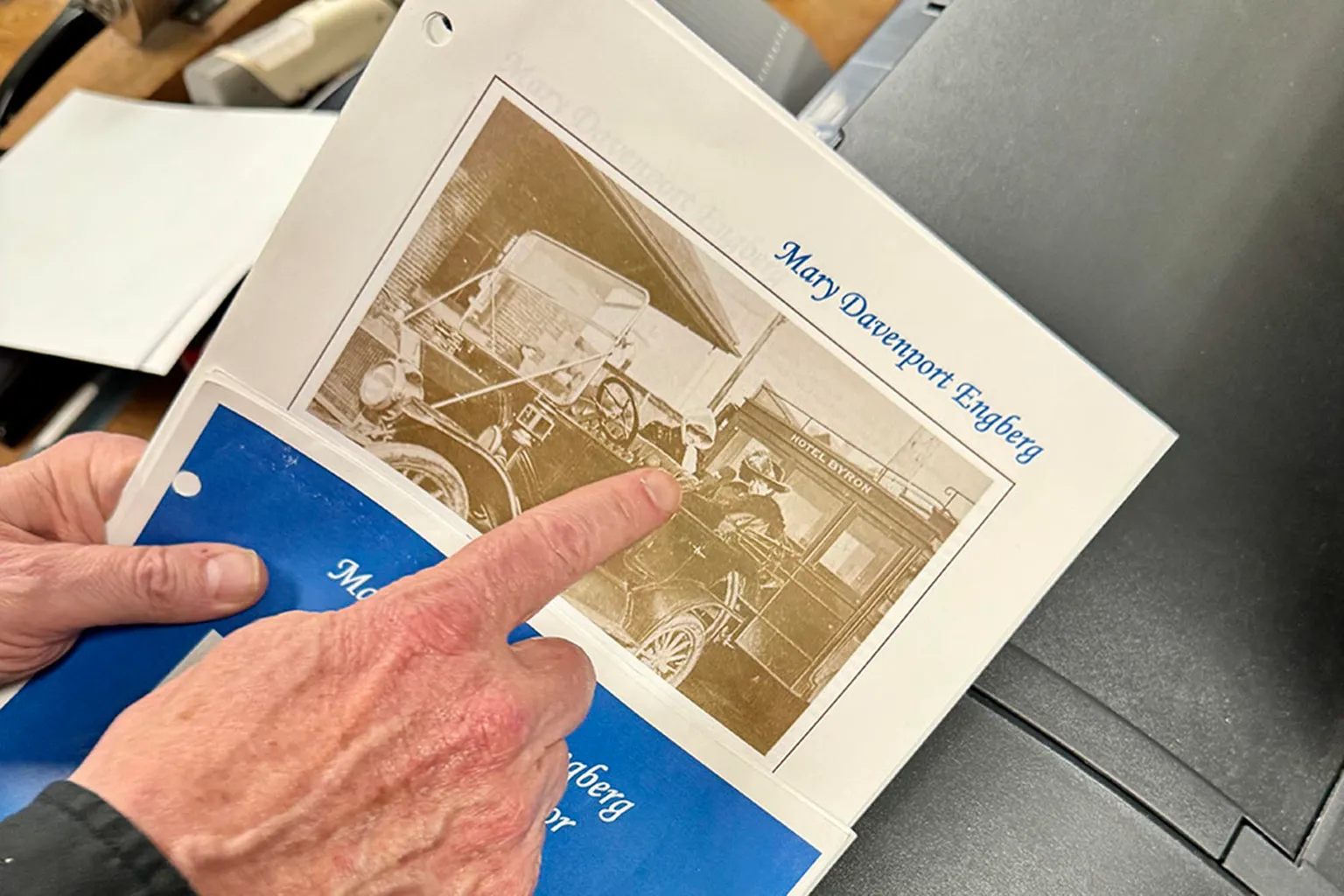

“Madame Engberg would inspire generations of musicians in Bellingham,” says Jeff Jewell,

Whatcom Museum archivist and researcher. (Stacee Sledge photo)

This article is part of the Seattle Times Giving Guide special section. Read more here.

More than a century ago, when the clatter of horse-drawn carriages still echoed along Bellingham’s streets, music lovers gathered in the small but growing city to witness something remarkable — a symphony orchestra conducted by a woman.

Her name was Mary Davenport Engberg, and in 1910 she became one of the first women in the United States — and the first in Washington — to conduct a professional orchestra composed of both men and women. Long before the term “glass ceiling” entered our vocabulary, Engberg quietly shattered it in the classical music world with her baton.

“Madame Engberg would inspire generations of musicians in Bellingham,” says Jeff Jewell, Whatcom Museum archivist and researcher.

Today’s Bellingham Symphony Orchestra audiences no longer arrive by streetcar or wear feathered hats, but the purpose of gathering remains the same: to experience something human and transcendent, together.

A woman in a long, white Victorian dress.. Caption: Mary Davenport Engberg (Courtesy of Whatcom Museum)

Mary Davenport Engberg (Courtesy of Whatcom Museum)

A violinist and composer, Engberg was part of Bellingham high society and its women’s clubs.

“She and her peers had staff to help run their homes; they spent the money of their rich husbands — captains of local industry — and directed it to the community good,” Jewell says. But Engberg stood apart in that she also chose, and very much wanted, to work.

“She’s raising children,” says Jewell, “but she’s also a music teacher and on the faculty of the Normal School (now Western Washington University). Music was like a religious passion for her; she felt it was vital to a community’s health.”

To that end, Engberg cultivated musicianship. Many instruments weren’t represented in Bellingham, so she encouraged students: Had this young person heard of the bassoon? She was happy to buy them one. She furnished instruments to many aspiring musicians, all part of her dream to create a civic symphony.

A bald man wearing a dark sweater stands in front of an exhibition of black-and-white photos at a museum.. Caption: “She and her peers had staff to help run their homes; they spent the money of their rich husbands — captains of local industry — and directed it to the community good,” Jeff Jewell says. (Stacee Sledge photo)

“She and her peers had staff to help run their homes; they spent the money of their rich husbands — captains

of local industry — and directed it to the community good,” Jeff Jewell says. (Stacee Sledge photo)

Engberg made her debut as a violinist in 1903, in Copenhagen, and toured Europe extensively. During her years abroad, she struck up a friendship with renowned violinist Maud Powell.

In 1912, Engberg created the 50-member Davenport Engberg Orchestra in Bellingham. By 1917 — having drawn Powell to perform on three different occasions — Engberg’s orchestra officially became the Bellingham Symphony Orchestra.

“Powell was among the first prominent violin soloists — possibly the first of international stature — to perform on the West Coast,” says Bellingham Symphony Orchestra violinist and concertmaster Dawn Posey. “And Mary Davenport Engberg brought her here.”

Posey learned of Engberg just last year, and the Powell connection to Bellingham in the early 1900s. She immediately shared it with BSO Executive Director Gail Ridenour and Music Director Yaniv Attar.

“I had been planning a different concerto for our summer performances,” Posey says, “but learning that Maud Powell had played Mendelssohn in Bellingham, I wanted to do the same, to honor her.”

“When Dawn told us the story of Madame Engberg, we knew instantly how special the connections were,” says Ridenour, who inspired an exhibit currently on display at the Whatcom Museum celebrating Madame Engberg and the Bellingham Symphony Orchestra’s history.

Having left her musical mark on Bellingham, Engberg went on to create the Seattle Civic Symphony Orchestra in 1921, nurturing local talent for the Seattle Symphony Orchestra, which she then conducted through 1924. She founded the Engberg School of Music in Seattle and continued teaching violin until her death in 1951.

Perhaps Engberg’s most enduring contribution wasn’t her pioneering leadership — it was her understanding of what music means to a community. In a frontier town still defining itself, she used music to draw people together, to lift spirits and to offer moments of beauty amid uncertainty.

That same spirit remains alive in Bellingham today. The Bellingham Symphony Orchestra is a thriving ensemble and resident orchestra of the historic Mount Baker Theatre.

And much like world-famous Maud Powell was drawn to perform in Bellingham, Yo-Yo Ma takes the stage with the BSO in April 2026, inspired by its longstanding “Harmony from Discord” series, which focuses on music that transcends oppression and raises historically oppressed voices and composers.

When Engberg lifted her baton in Beck’s Theatre more than a century ago, she wasn’t just conducting musicians; she was conducting a vision — a belief that beauty and belonging could bloom through music. That belief still resonates every time the music begins.

The Bellingham Symphony Orchestra has been sharing live classical music with its community for more than 50 years — and is looking forward to the next five decades.